Collisions

Contents

Collisions#

So the first thing we need to handle to make a work hash table is to handle a collision . A collision occurs if two values that are added to the hash table end up hashing to the same index. This causes a problem with our current approach since we use the hashing trick to instantly know which index a particular value belongs in.

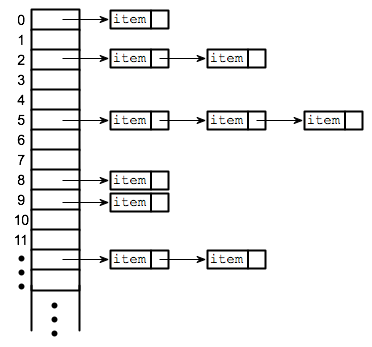

It turns out though, this is relatively easy to fix by allowing our hash table to store multiple values at a single index. The way this is commonly implemented is with an approach called separate-chaining , where we make a chain of values at a particular index that is linked together. A hash table that uses separate-chaining to handle might look like the following image. Now, instead of each index of the hash table storing a single value, it stores these chains of values so it can handle collisions. For those that have taken CSE 143, this chain is implemented as a Linked List.

It’s not sufficient enough to say that we will store these multiple values at an index in a chain, we need to re-specify how add and in should work with this new structure.

To check if a value is

inthe hash table, you still use the hashing trick to figure out which index it should go to. However, now you can’t immediately say whether or not the value is at the table, because you will need to search through the values at that index to find the one you are looking for. So this involves starting at the first value in the chain and looping until the end of that chain to find the target value. If the value you are looking for is nowhere in the chain, you can confidently returnFalsethat the value is in this set.When you

adda value, you still use the hashing trick to identify which index it belongs in. You also generally check to make sure the value isn’t already in this chain sincesetsdon’t allow duplicates. If the value is not present in the chain at that index, then you can simply add a new link to the chain. By convention (and for simplicity), we always add the value to the front of the chain. So that means if a chain hasitem1->item2(whereitem1is the front) and we additem3to it, the chain will now becomeitem3->item1->item2.

That’s basically it! Now we have a working hash table that can handle collisions!

Efficiency#

You might be wondering: is this actually going to always be \(\mathcal{O}(1)\) lookup for a value since this new approach now requires us to loop through a chain of values? That’s a very astute observation and definitely something we should be worried about!

It turns out under some reasonable assumptions (particularly, that you use a good hash function as we will describe in the next slide), it should be unlikely for collisions to happen in the first place. This means the number of items in a single index should be relatively small in comparison to the total number of items in the whole hash table (the \(n\) in \(\mathcal{O}(n)\)).

To make sure this is true, a hash table has to care about its load factor , which is the average number of elements in the table per index ( num_elements / size_of_table ). If the load factor is too large, it is more likely for collisions to happen since the table is more full. To fix this, we generally make sure the load factor is small by rehashing if the hash table gets too crowded. Rehashing is a process of building a new, larger hash table and putting all the values in the original table into this new one. When you rehash, the collisions you saw before are unlikely to happen again, since you will be modding by a different table length (e.g., even though 2 % 5 == 7 % 5 , it’s not the case that 2 % 10 == 7 % 10 ).

By doing this process whenever the load factor gets too large, we can control the number of collisions that will occur by reducing the load factor any time it exceeds some threshold. And remember, a lower load factor means fewer elements per bucket to search through making sure our searches are fast. While the rehashing process is computationally expensive, it happens infrequently so most operations on the hash table are constant time.