Differential Privacy

Contents

Differential Privacy#

In the last slide, we saw a video about the 2020 US Census and privacy guarantees they make using this tool called differential privacy . Let’s dive in a little into what this term means and one specific technique to achieve it.

What is Privacy#

Before arriving at an understanding of differential privacy, we should first outline what privacy means in the first place. What does it mean for a system to ensure the privacy of an individual? A slightly ambitious definition might say that a data analysis protects the privacy of the individuals whose data it uses with the following definition: There should be no risks at all for the people whose data is involved in the analysis.

In other words, this lofty goal says you can never come under harm (however we choose to define harm) by having your data present in the analysis. If we meet that definition, then we would say our analysis protects the privacy of the individuals in the analysis.

This sounds like a great idea in theory, but we’ll see that it’s just a little too ambitious to meet practically. To see why, let’s explore the following thought experiment outlined in The Ethical Algorithm:

Imagine a man named Roger—a physician working in London in 1950 who is also a cigarette smoker. This is before the British Doctors Study, which provided convincing statistical proof linking tobacco smoking to increased risk for lung cancer. In 1951, Richard Doll and Austin Bradford Hill wrote to all registered physicians in the United Kingdom and asked them to participate in a survey about their physical health and smoking habits. Two-thirds of the doctors participated. Although the study would follow them for decades, by 1956 Doll and Hill had already published strong evidence linking smoking to lung cancer. Anyone who was following this work and knows Roger would now increase her estimate of Roger’s risk for lung cancer simply because she knows both that he is a smoker and now a relevant fact about the world: that smokers are at increased risk for lung cancer. This inference might lead to real harm for Roger. For example, in the United States, it might cause him to have to pay higher health insurance premiums—a precisely quantifiable cost.

In this scenario, in which Roger comes to harm as the direct result of a data analysis, should we conclude that his privacy was violated by the British Doctors Study? Consider that the above story plays out in exactly the same way even if Roger was among the third of British physicians who declined to participate in the survey and provide their data. The effect of smoking on lung cancer is real and can be discovered with or without any particular individual’s private data. In other words, the harm that befell Roger was not because of something that someone identified about his data per se but rather because of a general fact about the world that was revealed by the study. If we were to call this a privacy violation, then it would not be possible to conduct any kind of data analysis while respecting privacy—or, indeed, to conduct science, or even observe the world around us. This is because any fact or correlation we observe to hold in the world at large may change our beliefs about an individual if we can observe one of the variables involved in the correlation. So just from this example, it seems very difficult to actually ensure the protection of privacy. Using our idea of privacy above, the researchers could never run this study and say it respects privacy since it's learning a true, but negative correlation about the world. However, this might make us think our original definition of privacy might be a little too strict. In this scenario, it wasn't the case that Roger's participation in the study changed the outcome. He was just one data point out of many and the underlying trend discovered was something true about the world, not something dependent on Roger specifically.

This concept of Roger’s individual participation not actually mattering in big-picture outcome is actually the key inspiration for how we can come up with a definition of privacy that is feasible to satisfy. This definition of privacy is called differential privacy.

Differential Privacy#

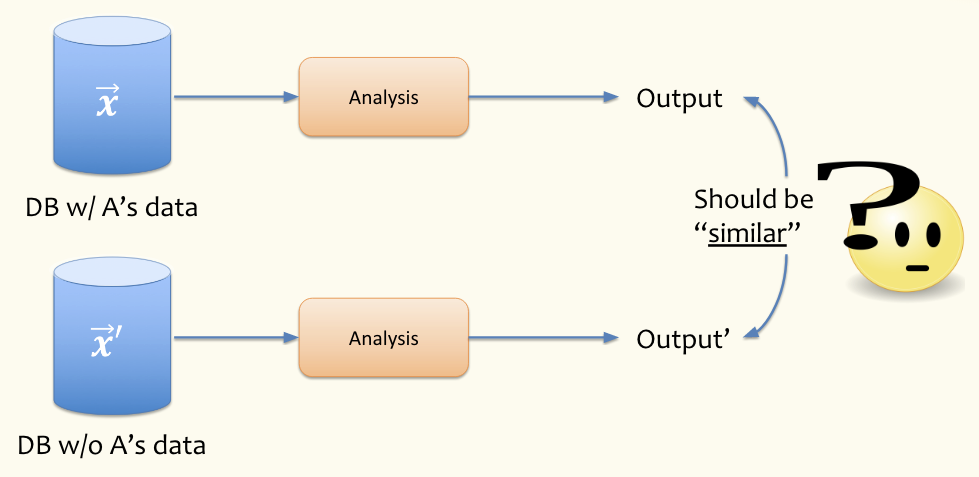

At a very high level, differential privacy says the results of a study shouldn’t rely too much on the participation of a single individual. To conceptualize what this means, we think about two “parallel universes”, one where Roger participates in the study and one where he does not. If the results of the study are similar with and without Roger’s participation, we would say that Roger’s privacy is not violated.

To understand this process pictorially, see the image below. The A in the labels can correspond to Roger in our example. So we consider the world with Roger’s data and the world without and we want to make sure that in order to respect his privacy, the results of these two analyses should be similar.

We can’t require the output of the analysis is exactly the same since then the output of the analysis must not depend on the presence of any individual (which would make the inclusion of people useless). So our hope is to get an output that is at least close with or without an individual.

Hence, the term differential privacy is introduced. The “differential” in this term represents the two universes that do or don’t contain your data, and we say this system is differentially private if the results in these two universes are similar. As mentioned in the video, we don’t think of differential privacy as a “yes” or “no” endeavor. Instead, we have a sort of “knob” we can tune to control how much privacy we want. So technically we say a system is \(\varepsilon\)-differentially private, where \(\varepsilon\) controls how similar we want the results to be.

If we choose \(\varepsilon\) to be small (near 0), that means we will require that the results of the analysis must be VERY similar, thus enforcing a stricter notion of privacy (that may or may not always be possible to achieve). In fact, letting \(\varepsilon = 0\) we will require the analysis with and without your data is exactly the same; this means the result of the data analysis must be independent of any person’s data in it! If we choose a larger \(\varepsilon\) this allows for more changes in the output of the analysis if your data was removed, thus having a weaker notion of privacy since we let the result of the analysis vary more. In some sense, you can interpret the \(\varepsilon\) as the allowed measure of how “unprivate” your system is allowed to be (larger value means less privacy).

Optional

Optional: You do not need to understand the content inside this box.

If you’re curious how this requirement for \(\varepsilon\)-differential privacy is actually written mathematically, we write the definition out below. We can’t go into all the math behind this (e.g., what the probability is defined over), but it’s a starting point if you want to learn more!

Let \(\mathbf{\vec{x}}\) be a database of individuals’ data. Let \(\mathbf{\vec{x}}'\) be an alternative reality version of the dataset where a single person’s data was removed. Let \(M\) be some mechanism that does a computation on the database (e.g., compute an average). In otherwords, \(M\) is a function that takes a database and returns the result of some computation on that database \(M(\mathbf{\vec{x}}) \in \mathbb{R}\).

A mechanism \(M\) is \(\varepsilon\)-differentially private if for all subsets \(T \subseteq \mathbb{R}\), and for all databases \(\mathbf{\vec{x}}\), \(\mathbf{\vec{x}}'\) that differ at exactly one entry,

Note from this definition above, you can see the behavior we described earlier that \(\varepsilon=0\) requires the probability of some outcome to be very similar while a larger \(\varepsilon\) allows the results of the two databases to vary more.

Note, this definition only applies to changing the database by one person. The analysis is differentially private if it applies to every person in the dataset (no matter how typical or atypical their data is), but the definition is only about removing one person at a time to make sure there aren’t differences in the result. There are extended notions of differential privacy that apply to groups of peoples, but the formulations are slightly more complex.

In the next two slides, we will see two concrete ways that you can achieve this notion of differential privacy.

Limits of Differential Privacy#

While differential privacy is quite strong, it is not able to guarantee the “no harm” goal that we originally tried to set up. That goal of “no harm” is too strict to feasibly meet (see our thought experiment with studying smoking and lung cancer). What differential privacy does guarantee in this scenario is that Roger’s participation or lack thereof do not impact the ultimate results of the study. It turns out this is equivalent to the condition that you can’t tell if Roger’s data was used in the result of the study. So differential privacy can protect anyone from knowing if Rodger participated in the study, but it can’t prevent the learning of some general truth about the world (smoking is linked to cancer).

We also pointed out that differential privacy is with respect to the potential removal of a single person. It says nothing about the privacy of groups of people. There are many differentially private systems used in industry to this day, from Google to Apple to Strava (fitness tracking). Many systems they use can guarantee differential privacy which means you can’t know if some individual was present in the data or not. However, this can still lead to some complications when considering groups.

So take Strava, a fitness tracking app, for example. One type of analysis they do is looking at heat maps of the world to find popular running locations. The system they use to analyze data is differentially private, so it’s not possible to get information about a single person’s route. It turns out that analyses like this work well in large US cities where many people have Strava devices, but things get more complicated if you look at data coming from poorer or war-torn regions like Syria or Afghanistan (many people in these areas don’t have Fitbits or use Strava).

One exception to that though, is that US military personnel do operate in those regions and are more likely to use such a device (in fact, it’s actually encouraged by the US military). So looking at the Strava data, you can see (in aggregate) running paths like in Afghanistan’s Helmand Province actually correspond to military bases, not all of which are supposed to be known publicly!

This is not a fault of differential privacy! Differential privacy (as we have defined it) is all about protecting the information of an individual in an analysis. The system is working as intended since you wouldn’t be able to look at their analysis and find information about a particular soldier in the data. But differential privacy makes no claims about how people behave in groups and doesn’t have a notion of group privacy built-in. There are extensions to differential privacy to allow for protecting groups of people, but the simple approaches people use so far work for very small groups of people, not entire platoons of soldiers.