Worldview / Limitations of Fairness

Contents

Worldview / Limitations of Fairness#

So far in this lesson, we have discussed just a few of the many possible definitions of fairness in the specific context of group fairness . While we didn’t explicitly talk about how these definitions conflict, it should not be surprising that different fairness on decisions might impose completely disparate requirements on your model’s outputs that can potentially conflict with each other. In the last slide, we also talked about a general tradeoff between fairness and accuracy. Given both of these trends, it only highlights the importance of keeping people informed and in the loop to decide which fairness definition to use and what level of tradeoff between accuracy and fairness is.

Our goal in this last slide is to provide some terminology and concepts to think about that can help in making a decision on how to treat the relationship between people and your data. This slide is based on the discussion Friedler et al. (2016) which is an interesting survey of terminology but quite mathematically complex. In this slide, we present a more intuitive take-away of their high-level contributions:

Being explicit in how we consider our data is gathered and what we are trying to model. This is a step that’s often ignored in the practice of ML

Defining individual fairness and group non-discrimination

Defining two common world-views that are taken in how people believe the data should be viewed.

Showing that these worldviews and their associated notions of fairness or non-discrimination are in contradiction to each other.

Construct Space#

The first contribution Friedler et al. made was trying to make explicit some of the implicit assumptions we make when making ML models, particularly what the data we are working with even means. For example, let’s go back to our example of predicting college admissions. We will take data about student’s academic performance (e.g., high school grades, SAT scores, etc) and maybe their extracurriculars and try to predict whether or not they will succeed in college.

Now something you probably haven’t thought about in this context, is that we don’t actually care about high school grades or SAT scores themselves. What we care about is trying to find some signal that correlates with collegiate success. So the assumption is that we can use these measurements as a proxy for some underlying qualities like intelligence or grit (perseverance). If that assumption is correct, then this process is well-founded. But what if SAT score is not a good measurement of intelligence (spoiler: it does a bad job at measuring intelligence)? What are we even doing if we are working with data that is not correlated to the concepts of interest?

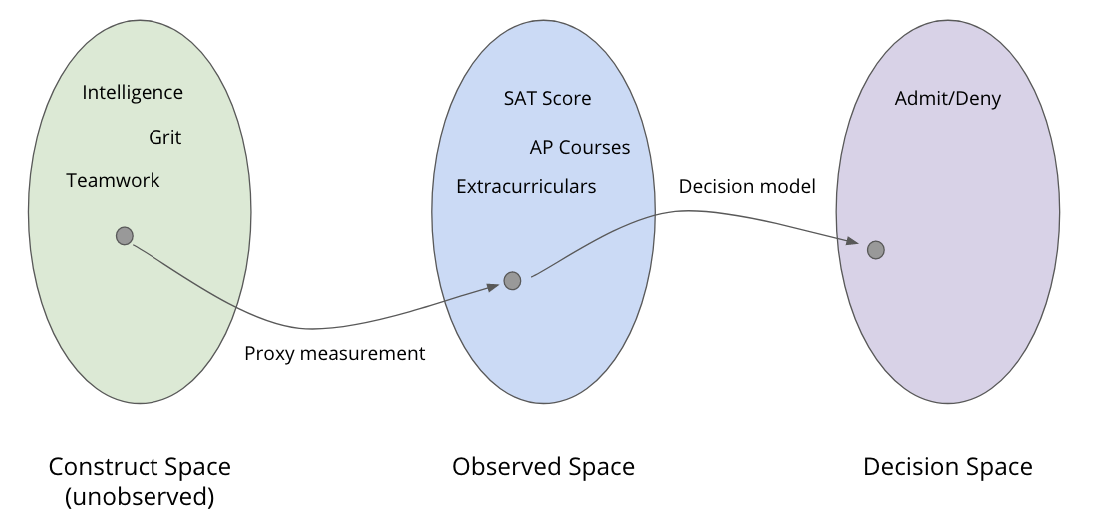

Friedler et al. introduce this notion of three spaces in an ML modeling task. These spaces and their relationship are shown pictorially in the image below.

The Construct Space is the set of abstract qualities we actually care about. So maybe for college admissions, we care about intelligence, grit, and the ability to work on a team. The problem is all of these notions are abstract, and there is usually not a way of directly measuring them for a particular person.

The Observed Space is the set of data we are able to gather about people. The hope is that we can find measurements that we are able to correlate with these ideals in the Construct Space. We will use this Observed Space data to make predictions about the future.

The Decision Space is the final step of a pipeline, which is the ultimate decisions of the model. In our college admission example, the Decision Space is the set {Admit, Deny}.

So the importance of their contribution is trying to be explicit that the data we have (Observed Space) may or may not actually be related to the quantities that we actually care to use in our prediction (Construct Space). What can we say about fairness in the cases when we are able to make good proxy measurements, and what about in the case we can’t?

Individual Fairness#

So far in the earlier sections of this lesson, we have only been discussing notions of group fairness or trying to prevent discrimination . What might a definition of fairness mean when considering individual people rather than groups of people? Friedler et al. provide a relatively straight-forward approach to defining individual fairness

A system is individually fair if people that are close together in the Construct Space receive similar decisions in the Decision Space.

In other words, if two people are near-equal in all qualities of interest in the Construct Space (e.g., for college admissions we cared about intelligence and grit in our example) then they should receive similar decisions. That’s a very straight-forward notion of fairness, but unfortunately, it’s impossible to ensure it’s true unless you make assumptions on how the world works.

Remember, we generally don’t have access to the Construct Space (e.g., the abstract notion of intelligence) so it’s impossible to directly measure if two people are close together in the Construct Space. The only things we do have access to are the Observed Space and we have no idea if those proxies are or aren’t good representations of the Constructs we care about.

This means that we have to make an assumption of worldview and decide how we think the world works. Friedler et al. outline two worldviews that are commonly taken by ML practitioners which we will talk about in the following sections.

Worldview 1: What You See is What You Get (WYSIWYG)#

The simplest assumption you could make about how the world works is to assume that your Observed Space is a good representation of the Construct Space. The authors call this “What You See is What You Get” (WYSIWYG) . In our college admissions example, the WYSIWYG worldview says that we are assuming SAT Score does correlate with the abstract quantities of interest in the Construct Space like intelligence.

Note that this is a statement of an assumption. This is not saying that it’s the right thing to do, but a statement that many people implicitly assume is the case. When you train a model on data, you might be making the implicit assumption that data is representative of the qualities you are interested in modeling.

Now, if you make the WYSIWYG assumption, guaranteeing individual fairness is very simple. Under this assumption, you can use the Observed Space data as a quality proxy for the Construct Space. So to ensure individual fairness under the WYSIWYG worldview, you just have to look at applicants that have similar features in the Observed Space and ensure they receive similar outcomes.

This isn’t the only worldview though. What would we do if we don’t think the Observed Space is representative of the Construct Space?

Worldview 2: Structural Bias#

What might we do if the Observed Space is not representative of the Construct Space? What if there was some societal or systemic factor that affected how the data in the Observed Space is measured, that cause changes in how an individual looks in the Observed Space for reasons outside of their control?

To discuss this, we will continue with our toy example of college admissions in a world with the Circle/Square race, but this discussion generalizes to real-world scenarios as well. So we will focus our discussion right now on the groups of Circle people and Square people. In many real-life scenarios, the presence of structural bias can cause problems in how data reflects reality. These biases in data can then affect the ultimate decisions of the model, leading to potential discrimination against a group.

To be careful, Friedler et al. describe two possible sources of discrimination in an ML pipeline:

Direct Discrimination (in the model that takes data from the Observed Space to the Decision Space). Direct discrimination would be the cartoonishly evil example of taking someone’s race as a possible value in the Observed Space and intentionally harming people of a particular group. In many cases, doing something involving direct discrimination is explicitly illegal.

There is also a subtler way that a system can learn to discriminate, and that comes from biases in the data itself. This is referred to as Structural Bias (in the mapping from the Concept Space to the Observed Space) where the data for different sub-groups looks different than it should be based on the Construct Space. This then leads to the model of “fairly” treating the data in the Observed Space, then to biased decisions, since the data it learned from reflects the structural bias of society. In our example of college admissions, this can clearly happen when race is strongly correlated with socioeconomic status. Groups that tend to be better off economically can are more likely to be able to afford test prep resources like SAT prep, which then leads to overly high SAT test scores when compared to their peers that could succeed just as well if they had the means to afford the same preparation.

So in this worldview where there is a presence of Structural Bias, the goal of a model is to have non-discrimination. The authors are very careful to avoid calling this fairness to avoid confusion with the notion of individual fairness since we will see later that these concepts might actually be in contention.

So what do we do when we believe there is Structural Bias in our data? We very commonly make another assumption called We’re All Equal (WAE) . This assumption recognizes that Structural Bias is present and makes the additional assumption for the task we are trying to model, race should not cause a meaningful difference in things like academic preparation. So this is not saying that different subgroups are completely equal, but that they should be equal enough when considering things relevant to the task at hand. This means then that any differences observed in groups in the Observed Space should be the result of structural bias rather than some inherent quality of the group itself.

So when do we make this assumption? Well, this entire lesson we have somewhat implicitly been making this assumption with the notions of group fairness we have introduced. The whole idea of equal opportunity and other group fairness metrics is to explicitly encode that different groups should have equal treatment since any differences observed are the result of factors outside of an individual’s control.

How can you verify the Structural Bias and WAE worldview? Well, that’s not really possible since it’s a belief or a worldview. Just like with WYSIWYG, we don’t have access to the actual Construct Space so we have no idea if the Observed Data is actually representative or not.

Conflicting Worldviews#

So we have set up yet another dichotomy here where the right answer depends on our context and should be made carefully by people, not by an algorithm. Even though we haven’t introduced a definitive answer on which worldview you should use, hopefully, this terminology helps you reason about how you think the world works. And to be clear, the worldview you use should change for each problem and should be shaped by our values on how we think the world works. Even if this decision doesn’t make you comfortable, you have to make it whenever you do a modeling task since it turns out these worldviews are contradictory to each other and lead to conflicts in being able to achieve individual fairness and non-discrimination.

Unfortunately, these worldviews and notions of fairness/non-discrimination are not compatible. WYSIWYG and Structural Bias are in exact contradiction if we are looking at data that shows differences between particular subgroups. And it turns out each worldview only lends itself to one of fairness or non-discrimination.

If you assume WYSIWYG

Individual fairness is easy to achieve!

Attempts at non-discrimination may violate individual fairness. Non-discrimination may force you to reject or accept applicants to reach some notion of parity between groups, which at an individual level may be unfair since similar people in the Construct Space may receive different outcomes.

If you assume Structural Bias and WAE

Non-discrimination is possible! We just need to use one of the group-fairness metrics discussed earlier (e.g., equal opportunity).

Attempts to meet individual fairness may actually result in discrimination. Remember, with individual fairness we have to use the Observed Space as our stand-in for how close people are in the Construct Space. But under the worldview where we admit there is Structural Bias, using this observed data as our notion of fairness may lead to discriminatory outcomes to particular groups.

While that sounds weird at first, you have to remember that individual fairness only cares about individuals and makes no claim about how groups as a whole are treated. In a very real sense, it is very unfair to individuals of a particular group to be judged by biased data that resulted from them belonging to groups they had no choice of.

In fact, this contradiction is actually the result of many real-world debates on how to handle discrimination in society. After learning the topics/terms presented in this paper, I started to hear the often unsaid assumptions in arguments for/against policy decisions like affirmative action. So while we don’t provide any answers about what worldview you should take on, hopefully, you find the terms empowering for how you might think about novel situations and how something may or may not be fair.

Take-away#

So it’s clear then that your choice in worldview has a dire impact on how you can define what is fair or what is non-discriminatory in your context. While we did not necessarily provide answers in this lesson, hopefully we inspired you to ask new questions about the data you are working with and what sorts of fairness you value in a system.

Note that the field of algorithmic fairness is still relatively new in the grand scheme of things. One of the seminal papers “Fairness through awareness” was only published in 2011. That’s less than a decade when many constructs you learn in school have been around for a lot longer. So even though we might not have a lot of answers now, there may be important developments that you can help work on in the future!

The important part for us though at this moment is to realize that there is work going on in this space, and it constantly reaffirms the need for humans to be part of the decision-making process and that we need to be explicit in what things we assume about the world.