Is Your Data Anonymous?

Contents

Is Your Data Anonymous?#

We generally provide our data to be used by researchers and stakeholders, but we generally have an expectation that they do not release confidential information that may negatively impact your wellbeing if that data were released. We share our data though because we hope that the data will help them improve outcomes for us individually, or the world more broadly.

Let’s focus on your health data for a second. When might you share information about your health with someone else? For example, you let your doctor record information about your health when you go to get a checkup so that they can better serve your health needs as they evolve over time (e.g., spotting a developing condition, or knowing you are allergic to a particular drug before trying to prescribe it to you). Other times, you may participate in health research to help scientists investigate trends in health or test new treatments that could potentially save lives in the future.

Whatever the reason, medical data is crucial in helping people make decisions on how to treat health. So in some sense, there is a huge impetus to make sure we can share medical information broadly with the scientific community so that progress in medicine and health could be made quickly. Clearly, though, we probably aren’t comfortable with any and all data about our health to be published in the open. Health is a deeply personal matter, and you may or may not want your health records out there in the public. Healthcare providers go to extreme lengths to make sure data about individuals remains private to avoid potentially violating an individual’s privacy. This already starts to bring up a notion of a tradeoff between the utility of data and the privacy of individuals in the data. We will explore this tradeoff more in this reading.

Perhaps you might be thinking of a first solution to this problem. If sharing data can be good for the world, but we want to protect the privacy of individuals, why not just remove any data that personally identifies a particular person. In other words, publish all of the health data we want, but make it anonymous by removing individually defining information (e.g., someone’s name, their social security number, or patient ID).

“Anonymous” Data#

As an example of an attempt to publish anonymous data, let’s go back to the 1990s when a group in Massachusetts decided to publish a dataset of hospital visits to help researchers study health trends. To avoid leaking potentially sensitive data, they removed information that uniquely identified individuals such as their name, address, and social security numbers. However, they felt like they should still include broad demographic data like sex, date of birth, zip code to help researchers.

The thought was that broad demographic data is supposed to apply to many individuals, so there is very little risk to an individual’s privacy by knowing a demographic detail about them. For example, if you knew a hospital record belonged to someone who is “Male”, there is very little you could do to trace back that record to Hunter since about half the population is “Male”.

So does this approach actually ensure privacy? It turns out it does not! The Ethical Algorithm describes the story of Latanya Sweeney quite well, so I’ll leave it to them to explain her work:

Latanya Sweeney, who was a PhD student at MIT at the time, was skeptical. To make her point, she set out to find William Weld’s [the governer of Massachusetts] medical records from the “anonymous” data release. She spent $20 to purchase the voter rolls for the city of Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she knew that the governor lived. This dataset contained (among other things) the name, address, zip code, birthdate, and sex of every Cambridge voter—including William Weld’s. Once she had this information, the rest was easy. As it turned out, only six people in Cambridge shared the governor’s birthday. Of these six, three were men. And of these three, only one lived in the governor’s zip code. So the “anonymized” record corresponding to William Weld’s combination of birthdate, sex, and zip code was unique: Sweeney had identified the governor’s medical records. She sent them to his office.

Very surprising! Even though in theory it sounded like an okay idea to publish broad demographic data, it turns out that the combination of many general details is possible to narrow down to identifying an individual. In later research, Sweeney estimated that 87% of the US population can be uniquely identified just by knowing 1) date of birth, 2) sex, and 3) zip code.

Your suggestion to fix this might be to just also remove those three columns, but there are two big challenges with that:

It wasn’t obvious at first that date of birth/sex/zip code would violate privacy, so how can you ensure that any columns you end up including don’t ultimately lead to the same mistake again?

Demographic data is extremely useful to researchers when it comes to identifying health trends. If you don’t know ANY information about a health record, it’s very hard to find any general health trends. So removing demographic details (e.g., sex or age) makes it difficult for the data to be useful to scientists.

So the challenge is: can we ensure individual privacy while still publishing demographic information?

k-anonymity#

Sweeney actually makes a return here in providing a clear, and rather elegant definition of how to ensure individual privacy while still publishing demographic data. She defines the concept of k-anonymity as a property that ensures at least some coarse level of privacy for an individual. A dataset is k-anonymous if any combination of “insensitive” attributes (e.g., sex, date of birth, zip code) appearing in the dataset match at least k individuals in the dataset.

There are generally two strategies for making a dataset k-anonymous:

Remove insensitive attributes to provide fewer ways to identify individuals

“Fuzzing” the data to make it a little less precise at identifying individuals. One example is showing an age-range rather than an exact age.

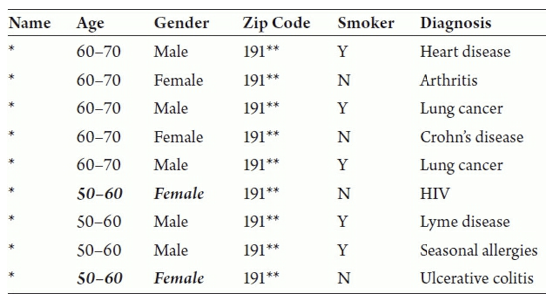

For example, you can see an example of a 2-anonymous dataset in the image below (taken from The Ethical Algorithm). This dataset is 2-anonymous because it narrows down the possible entries for an individual down to 2 rows for any insensitive data you might know about them. So for example, if you know someone named Rebecca is a 56-year-old female, you can only narrow down the dataset to two rows that could potentially belong to her (hence, 2-anonymous).

One nice thing about this definition is it allows you some sense of control over the tradeoff between privacy and utility. To ensure more privacy, you can make k larger to make sure there is a larger pool of people that you could potentially narrow down to (e.g., if you make k = 100 then any combination of insensitive attributes would only be able to narrow down to 100 people). To achieve k-anonymity for a larger k , it requires more aggressive fuzzing (providing less fine-level detail) or removing more insensitive attributes. However, a larger k will then require fewer specifics in the data to be released which may come at a cost of utility.

Limits of k-anonymity#

Sweeney’s work of defining the property of k-anonymity was a huge step in defining a notion of privacy, but it turns out to be a rather weak notion that doesn’t give us robust guarantees about the future.

Two big limitations of k-anonymity are:

k-anonymity does not compose across datasets: What this means is if I have two datasets that are individually k-anonymous, there is no guarantee that I can’t link them together to learn about an individual. That sounds a bit complicated, so lets try to get an intuition for what this means.

If you have two k-anonymous datasets, your guarantee can only narrow down to k people for dataset individually. However, the definition doesn’t take into account that you can potentially narrow down those two sets of k people to fewer people if you can find out commonalities between them. For example, consider Rebecca (the 56 year old woman). You can imagine that while Rebecca’s information is protected by k-anonymity in each separate dataset. But it’s possible for the k people from dataset 1 and the k people from dataset 2 to not overlap at all, except for Rebecca. That might still be a bit abstract without a concrete example, we promise that you can narrow it down by intersecting these groups from other datasets.

k-anonymity doesn’t necessarily protect an individual from potential harms: While it’s great that k-anonymity limits the exact amount of information someone can infer about a person, it still can potentially be used against someone. For example, if you know Jose is a 63-year-old male, you know that in this dataset shown above that he either has Heart Disease or Lung Cancer. While you can’t say for certain which he has, you know he might be one of those rows. That can still lead to some potential harm to Jose, imagine in a world where insurance companies could deny coverage to those with pre-existing conditions.

So to understand how we can make some stronger privacy guarantees, we have to explore a slightly more complex and more recent notion of privacy that is employed in many real-world systems today.