Memory Hierarchy

Contents

Memory Hierarchy#

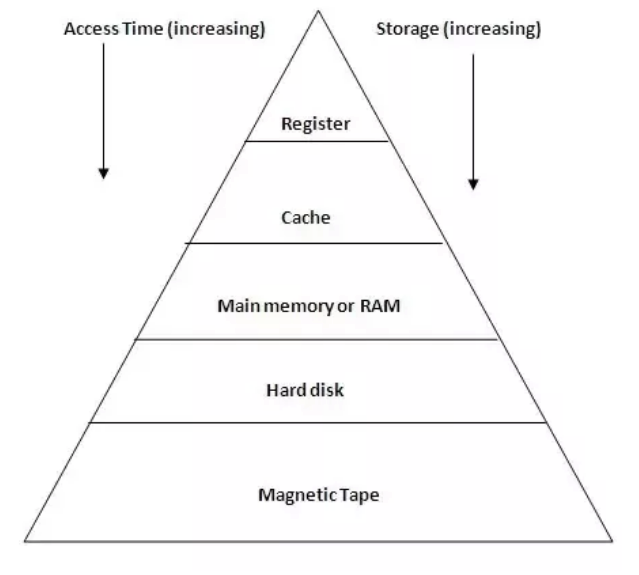

One thing that is important to know about memory is that there is a hierarchy of different types of memory that your computer uses that have various tradeoffs. We think about this as being a pyramid in the image shown below (your computer probably doesn’t have magnetic tape, that’s more old-school).

At the top of the pyramid is a register, which is an extremely small memory location located right on the CPU chip to store small, frequently accessed values. There is a cache (in reality, multiple levels of caches) that sit between your CPU and your main memory RAM to store frequently accessed pieces of memory. Caching is a general technique to store frequently accessed items so they can be accessed more quickly in the future. At the bottom, there is your hard disk (or more recently called Solid State Drives or SSDs).

As you go down the pyramid, the amount of memory variable generally increases. At the top, registers provide on the order of 1 kilobyte of space, while you can get up to terabytes of space on your hard disk or SSD. However, the increasing volume also comes at an increasing access time. This means it takes longer and longer for your computer to actually access the data as you go down the pyramid.

There is a cute analogy to give you a sense of scale how much slower reading/writing to disk is in comparison to accessing a register. Since people generally confuse you with millennials, they assume you also enjoy avocado toast as much as we do. So think of fetching data being like the processing of fetching an avocado to make avocado toast.

If your data is stored in a register, that’s like the avocado already being in your hand. There is almost no time to use the avocado to make avocado toast.

If your data is stored in the cache, that’s like the avocado is stored in your produce bowl on the counter. You have to walk over to the part of your kitchen with your produce bowl, grab the avocado, and walk back to your station. That takes on the order of a few seconds.

If your data is stored in main memory (RAM), that’s like needing to go to the store to buy an avocado! You have to get in your car or bike, go to the store, duck around people to maintain social distancing while buying the avocado before you can go back home. This takes on the order of 20 minutes.

If your data is stored in disk, that’s like planting an avocado tree, waiting for it to grow and produce fruit, and then making avocado toast from that! This takes on the order of multiple months.

The hard disk is a particularly extreme example. If you didn’t know, the name hard disk comes from the fact that it’s actually a physically spinning disk almost like a record player. This means to access memory on disk, you have to wait for these mechanical parts to physically move to align correctly to read the data you want!

Applications to Programming#

While the avocado analogy may be cute, it might not obvious why this is relevant to you as a data scientist if you aren’t working with writing programs at this low of a level. There are some pretty key takeaways from understanding this idea though.

First, notice that we talked about the fact that there are registers and caches above main memory. This is to help you as a programmer without you having to think of optimizing memory access as long as you program “normally”. What do we mean by “normal”? Generally, this means trying to follow locality. The designers of this hardware realized that almost all programs obey what they call “temporal locality” or “spatial locality”. Temporal locality means if you access a value, it’s more likely you will access it again in the future. Spatial locality means that if you access a value at index 0 in a list, it’s more likely that you will access the value at index 1 next rather than index 74. So this means when writing programs, try to avoid unnecessarily complicated logic that jumps around to different places in the dataset since these caching procedures generally try to speed up your program by assuming you will leverage these localities.

Second, realizing that reading/writing to disk is very slow and should be avoided being done frequently. There are some points where you will need to read/write to disk which is unavoidable (i.e., to read your dataset for data analysis), but ideally, you should try to avoid doing this frequently.

Third, is to keep this in mind when processing large datasets. Suppose I have a 50 GB CSV file for my final project and try to read it into Python using pandas.read_csv. If you remember correctly, my computer only has 16 GB of RAM, so how would it possibly read this file and store it in main memory for Python to access (see memory model of the last slide)? Your operating system does a clever trick called paging if you run out of RAM. Paging is a process of writing memory from RAM to disk if you were going to run out of space. This is nice from a continuity perspective, your program doesn’t completely break your computer even though you exceeded the RAM capacity, but very tricky from a performance perspective. This now means any time you want to access a new chunk of the dataset, your computer will have to go to and from disk to grab a new page of data that can fit in RAM.

The takeaway from the last point is that if you are working with large datasets, you might run into drastic slowdowns because of paging. As you are developing your code, it will help to develop with a small version of your dataset that will not cause these huge slowdowns. In some extreme cases, you might need to change your algorithm to work by reading the data only a small portion at a time to avoid paging in the first place.