Computer Memory

Contents

Computer Memory#

One of the resources your computer uses in addition to time is memory. In the abstract, memory is just any form of a way for your computer to “write down” information to access later. Memory is something you are probably familiar with as a user of a computer. Whenever you buy a computer, you specify how much RAM (short for Random Access Memory) you want (e.g., my Windows computer has 16 GB of RAM) and how much disk space you want (e.g., my Windows computer has 1 TB of disk space).

When talking about memory, we commonly are referring to the storage provided by your RAM; this is sometimes called flash memory or volatile memory. These names come from the fact that after you power your computer off, the memory stored there is lost! This is opposed to your disk storage (or persistent storage) which remains after shutdown. This is why if your computer crashes before you save, you lose your progress! While disk does have its benefits in the sense that it is persistent and can generally be larger in volume (notice that 500 GB of disk vs 16 GB of RAM), the big downside is it’s slow; more on this later.

Computer Memory (RAM)#

When we think of RAM from a programmer’s perspective, we really think of it as a giant array or list for us to write values to. So when we are talking about 16 GB of RAM, that’s one big array that lets us write 17,179,869,184 separate bytes (\(16 \times 1024 \times 1024 \times 1024\)) of data wherever we want; a byte is a number that stores eight ones or zeros (a bit).

Some programming languages, like that older one called C, let you access memory directly. More modern programming languages give you less access to do this since that comes with a whole host of security and correctness difficulties, but having some mental model of memory is sometimes helpful for understanding how your programs work.

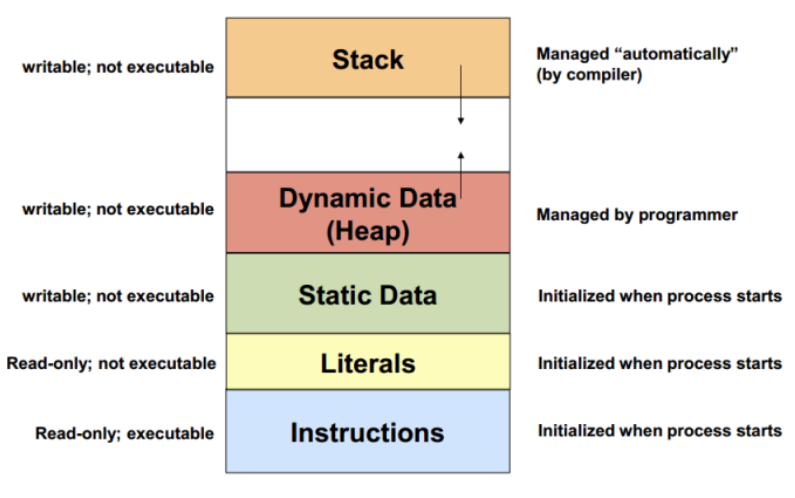

The following image shows a common layout of the memory allocated to a program by your operating system. There is no inherent restriction on how the RAM is partitioned for the program, but most programs generally separate areas of memory to store specifc things. While memorizing the names in the image below is not important, it’s good to realize that programs generally organize their memory usage in a systematic way.

Data in the “Stack” is data like your local variables in your functions.

Data in the “Heap” is for longer-lived data like objects (more on this later).

“Instructions” is where the actual code lives while it’s being run by the computer.

Creating Objects#

Every time you construct a new object in Python (or any programming language for that matter) it uses up a bit of your computer’s memory! This is because the object’s data needs to be stored somewhere and memory is the most convenient place to do that. They are generally created in the “Heap” portion of your memory.

This can cause problems if your program runs for a long time and slowly builds up a ton of objects. You have probably run into this before if you use a browser like Google Chrome or Mozilla Firefox; if you leave too many tabs open for too long, they sometimes cause your computer to freeze up because they use up so much memory after making so many objects!

Consider the following snippet, that will make a list of Dog objects. It’s designed purposefully to crash so if you run it, you will eventually get a memory error after some time.

class Dog:

def __init__(self, name):

self._name = name

dogs = []

count = 0

while True:

count += 1

dogs.append(Dog('Dog Number ' + str(count)))

# Print out number of Dogs periodically

if count % 100000 == 0:

print('Currently have', len(dogs), 'dogs')

A natural question is, who would ever make this many objects? You would! Your HW4 makes a TON of Document objects inside the SearchEngine (and those Documents have data structures that store values).

One thing that most modern programming languages implement is a garbage collector. A garbage collector is a process that runs behind-the-scenes that cleans up old objects that are no longer being referenced. This means any objects you made as local variables in a method will eventually be cleaned up automatically after that function has ended.